More databases should be single-threaded

Last night, I caused something on X by saying that (most) transactional databases should be single-threaded and aggressively sharded:

hot take: databases should be single-threaded

— Konsti Wohlwend (@konstiwohlwend) December 18, 2025

someone a long time ago decided that database shards should be multi-threaded. ever since then, we've had to worry about transactions, serializability, race conditions, and locking.

instead, we should have single-threaded shards,…

I have a lot more to say than would fit in a tweet, and the tweet also got more attention than I thought, so here's a lengthy blog post.

(There's no solution that solves every problem. But I hope I can convince you that aggressively sharded, single-threaded databases would suit you best more often than you'd think, even if you're "just" building a generic B2B SaaS app.)

The Status Quo

In essence, a traditional SQL database can write and read to rows in a table. It can also lock those rows, meaning that other writers may have to wait for the lock to be freed.

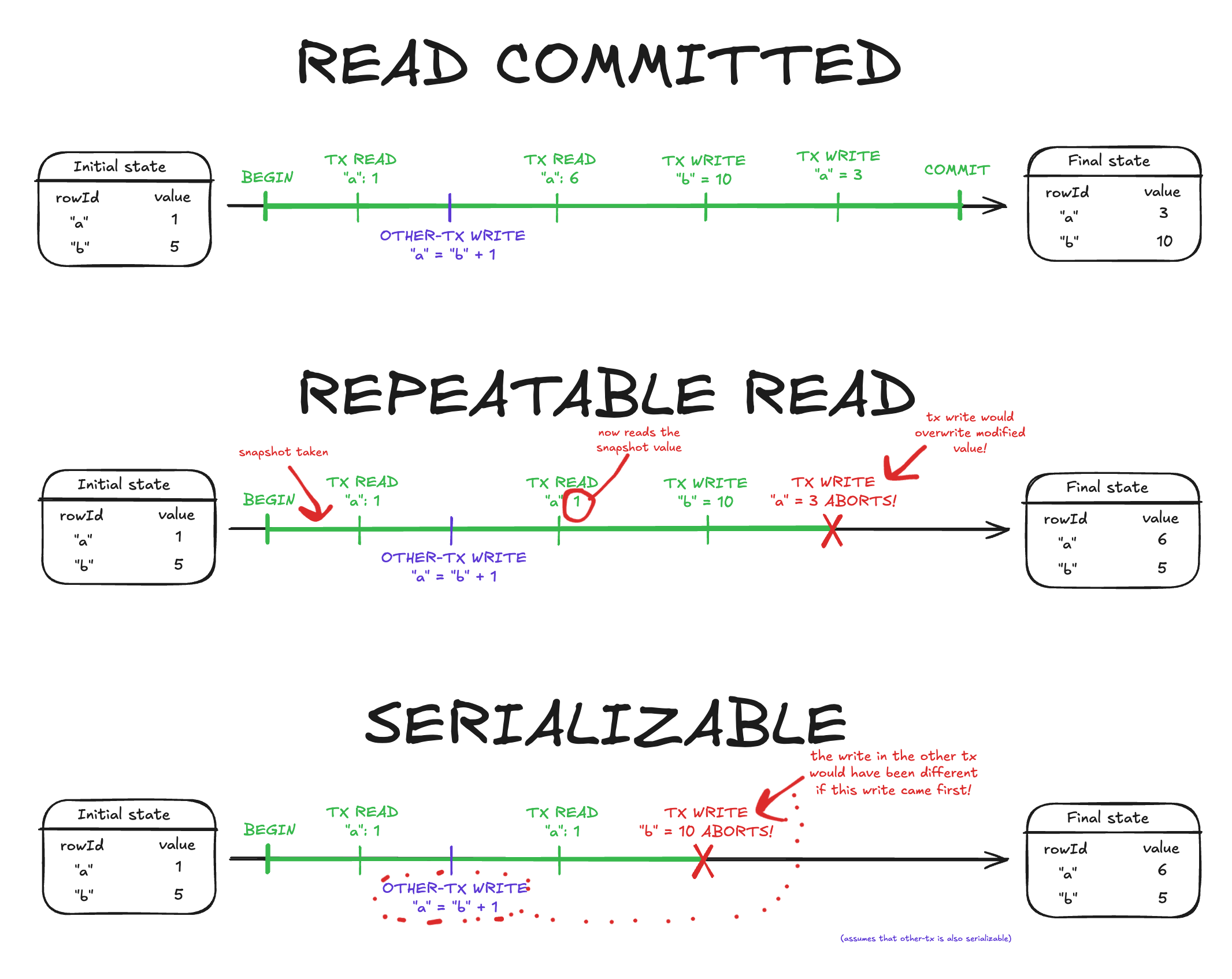

More concretely, Postgres has three different transaction modes:

- READ COMMITTED (default): Read statements will read the current database state. Write statements don't abort.

- If you read a row and then another transaction changes it, any future reads will return the new value.

- REPEATABLE READ: Read statements see a snapshot of the DB taken at the start of the transaction. Write statements abort the transaction if that particular row changed since the snapshot.

- Serialization anomalies (= writes end up out-of-order) are still possible. You also need to handle retries.

- SERIALIZABLE: Like REPEATABLE READ, but write statements abort the transaction if any dependent rows changed since the snapshot.

- Ensures a perfect ordering without serialization anomalies, but there is considerable overhead and retries are more common.

This has a lot of problems, though:

- When starting out:

- No one gets this right. IME most people think any transaction will make the entire block serializable!

- No one tells you when you get it wrong! There is no compile error, warning, or linter that gives you certainty. Like any parallel system, mistakes are hard to find.

- At scale:

- All three transaction modes use hard locks on writes! These don't block reads, but they do block other writes. If transaction A writes row 1 and then row 2, and transaction B does the same in reverse, chances are good you'll run into a deadlock.

- Under constant high load, serializable transactions may take many retries to finally succeed. It's impossible to tell how many.

- Those race conditions are nearly impossible to predict or debug when they happen in production. Best case you can just retry, worst case your data is corrupt.

- At scale, the locking overhead is deadly. In some cases, lock contention can take up a third of the entire DB load.

- It's explodes. More traffic means a higher % of failures. To counteract, you'll have to increase the number of retries, implying more traffic.

In many modern tech stacks, the database is the scaling bottleneck. Serverless infra lets you horizontally scale your compute to infinity. A database like this cannot. (This is not entirely to blame on the database.)

Instead, what many companies do is very pragmatic: If you don't have users, you ignore all these issues, don't use transactions at all, and hope for the best. Once you have users, you hire someone to "fix" the database for you. Simple.

But what if there was a better way?

One idea: Single-writer databases

One insight is that all of these problems are caused by conflicting writes. If your transaction never writes, you can just make it SERIALIZABLE READ ONLY DEFERRABLE and call it a day. Pretty simple.

So what if we just make sure that only one writer is writing at a time, and have a single global lock that ensures this? That way we always have perfect ordering.

Indeed, this is what SQLite does. And it works quite well! But there are still some problems:

- You are always limited by a single writer at scale. SQLite can do tens of thousands of writes per second, but you can't scale beyond it.

- There is still overhead in locking. Significantly so! SQLite in particular locks a file on the filesystem and has to coordinate with other threads (or even processes) to release it.

- If one writer stalls, everyone else is down. There is absolutely no write concurrency. Long queries are the same as DB downtime.

How hard can sharding be?

Here's an idea that comes up occasionally: If SQLite is good but doesn't scale, why don't we just shard it horizontally? Lev Kokotov from pgdog/pgcat wrote a great article on why you should shard your database early:

You’re probably wondering: what does the planner or the autovacuum have to do with sharding? The answer lies again with Occam’s razor: if our problem is a large and overutilized database, let’s make it smaller and use it less. This means splitting it into several smaller databases, also known as sharding.

It sounds great in theory! Unfortunately:

- Cross-shard queries are very difficult; you'll have to run a subquery on each shard and then join them all together

- Complex infrastructure: You'll need poolers, gateways, backups, and monitoring, and they all need to be aware of your shards

- Transactions across shards are hard. (This is often claimed to be impossible due to the Two Generals' problem but that's not quite true as long as you sacrifice either availability or partition-tolerance, but I have separate thoughts on that topic for a future blog post)

- This includes migrations that are not backwards-compatible. What if a migration succeeds on all shards but one? How can you roll them all back?

- The shard key is essentially immutable; changing it becomes a large migration crossing shard boundaries, which is extra hard

- No counters/autoincrement

- No cross-shard uniqueness or foreign key constraints

Two of these are new restrictions that can be worked around with new developer habits (counters -> timestamped uuids, db constraints -> app-level checks). Three others (infra, cross-shard queries, shard key mutability) can (mostly) be solved with better tooling (or an OLAP replica for analytical queries). What remains is transactions and migrations.

Let's look at transactions first. The classic example is that you have a payments platform with the user ID as the sharding key. You would now like to transfer cash from one user to another. How can you do this?

- Almost always you can just get around it by not using a transaction and accepting weaker guarantees instead. This is particularly true for read-only transactions.

- Change the sharding key. Maybe you can shard on the transaction ID instead, and accumulate the balances from there.

- Optimistic concurrency and/or sagas; you can read or apply some of the changes, and then revert or retry if you detect a conflict. This requires that the changes can be applied partially, such as by deducting first and granting second. For a split second, the cash is in no one's balance.

- As a measure of last resort, use a lock with a two-phase commit. This can be alright in some cases — remember that regular Postgres also locks rows that you write to in a transaction, although it would not block reads, and not incur any network latency. But once you do this, you are back in the world of deadlocks, and arguably much harder than it would've been to use Postgres in the first place.

On the migrations side, particularly those that are backwards-incompatible, we can divide the world's backends into roughly two buckets:

- Those that can afford some downtime

- Those that cannot afford any downtime

The status quo for the former is that they shut down the old server, migrate the database, then start the new server. The biggest difficulty is to replace "migrate the database" with "keep a transaction open on each shard and migrate them individually, until all succeed, then commit everywhere", although tooling can solve that. If a shard goes down during the commit phase, that may mean longer downtime.

The latter are less affected, as they are probably already doing expand & contract, which works perfectly fine across shards.

So is sharding worth it? Assuming you have a DB built for sharding and excellent tooling, you are losing out on:

- Counters & autoincrements

- DB-level constraints

- The ability for a single shard to scale beyond one core (sometimes this is not avoidable)

- Some cross-shard queries: Complicated JOINs are slower and transactions that absolutely NEED to be transactions become distributed systems

Compared to some query & parameter tuning on Postgres the answer is usually no. But if you're aware of the downsides, you'll be surprised by how often the answer can be yes!

Sharded single-thread databases

Assume we decided that our database will be sharded very aggressively. We stick to single-writer per shard. We still have many readers per shard; most apps are read-heavy so this should help.

Of course we can have multiple writer threads fighting for a shard-wide lock, but then we pay the cost of lock contention. There's a better way. We give each shard exactly one dedicated writer thread, and don't have to worry about parallelism at all.

Communication has to be cooperative. That means that each worker thread has to check periodically whether its timeout has been reached or the connection dropped mid-query.

Locks are also feasible. A naïve implementation would lock the entire shard, but that would obviously be bad. A better implementation would yield to the next query until the lock is released, just like async-await in programming languages with a cooperative event loop.

Of course, there can be other threads in the database doing useful tasks, such as managing connections and writing to disk. If we stick to one physical machine with many cores, reader threads (of which there could be many) could even access the database as a whole — counteracting the bad performance of cross-shard queries.

So what's the point? Essentially, we get conceptual purity:

- From a DX perspective, every transaction within a shard is always serializable, and never needs to be retried (except for database failure). There are no deadlocks, or write conflicts. This is just so so SO much easier to think about.

- The query parser can prevent queries that would act across different shard keys, unless a special flag is set to disable serializability.

- Fully horizontally scalable. No more excessive parameter tuning to maximize what you can get out of your cluster — just add more nodes.

- Extremely high per-thread throughput, as we don't need to sync with other threads. The shard's thread owns the data, and is the only one that can write to it.

- And finally, it's the peace of mind. A system like this is much more predictable, and while it can be restrictive, at least you can be confident there are no hidden race conditions.

The cost is that we have to shard on day 1. Is it really that bad of a deal?

Why hasn't this been done before?

It absolutely has been done! ScyllaDB and VoltDB, among others, are built on this exact concept. ScyllaDB calls this shard-per-core.

So what's the point of this blog post?

ScyllaDB and VoltDB have a very different target audience from the person that I hope I can reach here. They are targeting developers where scale is a requirement, not an option. Personally, I think that even the average web developer should be using sharded databases, if one for them existed.

It is also not new from the angle of the actor model of computation. Cloudflare Workers and Rivet are basically built on the same idea, and reinvent what a database is by going much further and even letting you distribute workers/actors globally.

But switching to paradigms like the actor model comes with a cost. I like most aspects of my current database. I would love to use a "mostly Postgres-compatible" DB where every transaction is serializable, has extremely good support for sharding, and the performance of a single-thread DB on each shard.

It doesn't solve all problems. But it would solve mine, and I think I'm not the only one.

Member discussion